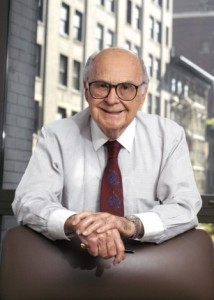

I recently participated in a roundtable discussion alongside one of our industry’s real pioneers (and a long-time mentor of mine) Harold Burson. The topic revolved around the future of public relations (don’t they all?). While the session’s hosts, PR Newswire and CommPro.biz, gathered a number of industry thought-leaders including Ketchum chairman Ray Kotcher and Weber-Shandwick CEO Andy Polansky, the soft-spoken, but always insightful Mr. Burson reigned supreme.

During the luncheon, he offered his take on content marketing, social media, and the ill-conceived rise of the job title “director of communications” as a better-sounding surrogate for “director of public relations” at most corporations. He linked its rise to the Watergate tapes wherein President Nixon advised his consiglieres to “PR this” or “PR that.”

This is not the first time I’ve heard Mr. Burson question the term communications as a descriptor for what we do as a profession. Over my 11 years at Burson-Marsteller, I took every chance I could to plop myself into one of his sturdy Stuckley chairs to solicit his opinion on a client quagmire or industry trend.

He simply felt that a company’s behavior, versus what it communicates, will dictate the quality of its relations to its many publics. Too many companies and organizations seem far too focused on how to manage outside perceptions, when it’s the actions they take that drive reputation (and business).

Today, ProPublica and NPR released a joint investigative report on the relief organization’s performance in the aftermath of two catastrophic storms that crippled much of the country – Isaac and Sandy. Â Their conclusion:

“Red Cross officials at national headquarters in Washington, D.C. compounded the charity’s inability to provide relief by diverting assets for public relations purposes, as one internal report puts it. Distribution of relief supplies, the report said, was politically driven.

During Isaac, Red Cross supervisors ordered dozens of trucks usually deployed to deliver aid to be driven around nearly empty instead, just to be seen, one of the drivers, Jim Dunham, recalls.”

Of course, the Red Cross defended its performance by issuing this statement to ProPublica and NPR:

“While it’s impossible to meet every need in the first chaotic hours and days of a disaster, we are proud that we were able to provide millions of people with hot meals, shelter, relief supplies and financial support during the 2012 hurricanes.

Still, these two rare and respected journalistic enterprises uncovered plenty of fodder to support their claim that the Red Cross was more focused on managing perceptions than fulfilling its mission.

“Richard Rieckenberg, who oversaw aspects of the Red Cross’s efforts to provide food, shelter and supplies after the 2012 storms, said the organization’s work was repeatedly undercut by its leadership.

Top Red Cross officials were concerned only ‘about the appearance of aid, not actually delivering it,’ Rieckenberg says. ‘They were not interested in solving the problem they were interested in looking good. That was incredibly demoralizing.'”

Few can deny the herculean challenges a sprawling organization like the Red Cross faces in the aftermath of a natural disaster. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that neither NPR nor ProPublica have much tolerance for anything that smacks of PR (except perhaps for their own PR staffs charged with publicizing their journalism).

Nonetheless, the allegations against the charity only reinforced the timeless advice Mr. Burson offeered during last week’s roundtable: it’s more about how an organization acts, and less about how they communicate that will ultimately drive esteem and prosperity.